The Lost Gardens of Leigh Farm Park and West Point on the Eno

By Cassandra Bennett, Recreation Operations Supervisor

Flower and vegetable gardens have accompanied homes for hundreds of years, though their layout and plants have changed with the passage of time. Today, only a few traces of these former gardens remain in Durham Parks and Recreation’s parks. While out on the trail, or a park’s open spaces, you may have spotted the privet, boxwood, wisteria, daffodils, various ivies, periwinkle, and yucca. Though some of these plants are considered invasive today, they are a steadfast reminder of what once were quintessential home gardens of their era. At Leigh Farm Park and West Point on the Eno, we are fortunate to have first-hand, family accounts of these well-tended outdoor living spaces. Both, just off their homes’ porch, were intensely personal reflections of their gardeners’ passions, preferences, and period.

The Leigh Garden at Leigh Farm Park

At nineteen, Ida Leigh, the youngest of Stanford’s twenty children, wrote that her grandmother, Nancy Hudgins, took great pride in caring for her flowers. Ida’s account comes from a school essay she wrote in 1893, of the garden in the 1870 and 1880s. While some of Nancy’s flower choices were out of fashion for the time, “grandmother did not make her selections to please other people, but these had been the favorite flowers in her youth and she preferred them now.”

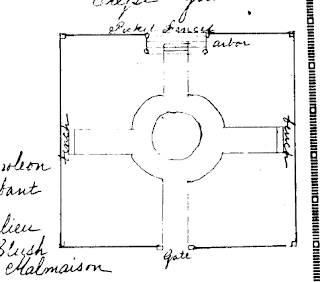

The half-acre garden was laid out in a typical Victorian Era fashion, with formal beds and walks, in the shape of a T. There was a rose arbor, under which she and her sisters “spent many an hour making crosses, rings, squares, etc of…the rose vine.”

Ida also remembers hyacinths in many colors, and “pulling the long blades…to hear them ‘sing,’” hoping not to be caught. Ida also recalls climbing on the garden’s picket fence to reach the fruit from orchard trees growing around the border. Of course, with all of these childhood antics, the Leigh children were careful not to be “seen by those who would have ‘reported us at headquarters.’” 1

The Garden at West Point on the Eno Meanwhile, the Mangum Garden, in contrast to Nancy’s at the Leigh House, had “a network of narrow paths [that] ran through the confusion of blooms within the picket fence” of the Mangum’s sprawling flower garden. There was also a hammock in the garden, near the home, which is featured in a family portrait Hugh Mangum took around 1895.

The garden hosted more than plants though, it was home to a lily pond with gold fish, a rock garden, a sundial, and even a flower shed dedicated to flower care. 2 All of these were typical of gardens in the early 20th century, and were in a constant state of change. One notable contrast was that Leo Mangum recalled mixing several inches of manure from downtown stables with the soil, despite access to popular commercial fertilizer. 3

Though very different, both gardens were labors of love. They were a place for family to gather, spend time outdoors, and even get a bit of exercise. At Leigh Farm Park, the 150-plus year old scuppernong vine is still producing, the naturalized daffodils bloom year after year, and there is privet everywhere. At West Point, you can find hyacinths, old roses, lilies, daffodils, yucca, and ivies scattered throughout the park. With a keen eye, maybe you’ll spot them when you’re in the park next.

Today, we continue the gardening tradition in the West Point Garden, where we grow and harvest food for members of our community. We partner with Hannah’s Kitchen and Root Causes (Duke Outpatient Food Pantry) during our harvest season, and donate about 300 pounds of produce a year.

_________________________________________________________________________________

1 Kenneth M. McFarland, “The Garden at Leigh Farm,” Bulletin of the Southern Garden History Society VII, no. III (Winter 1991): Appendix 9.

2 “The Mangum’s Garden, as Recalled by Their Descendants: Jack, Polly, Louise, and Vivian Vaughan, Pattie Scarborough and Eddie Rowe” (handwritten document, 1981), West Point Cultural Heritage.

3 Jack Vaughan, “Memories of the Mangum Family Garden,” 1981, West Point Cultural Heritage; and Patricia M. Tice, “Gardens of Change,” in American Home Life, 1880-1930: A Social History of Spaces and Services, ed. Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 190–208.

Flower and vegetable gardens have accompanied homes for hundreds of years, though their layout and plants have changed with the passage of time. Today, only a few traces of these former gardens remain in Durham Parks and Recreation’s parks. While out on the trail, or a park’s open spaces, you may have spotted the privet, boxwood, wisteria, daffodils, various ivies, periwinkle, and yucca. Though some of these plants are considered invasive today, they are a steadfast reminder of what once were quintessential home gardens of their era. At Leigh Farm Park and West Point on the Eno, we are fortunate to have first-hand, family accounts of these well-tended outdoor living spaces. Both, just off their homes’ porch, were intensely personal reflections of their gardeners’ passions, preferences, and period.

The Leigh Garden at Leigh Farm Park

At nineteen, Ida Leigh, the youngest of Stanford’s twenty children, wrote that her grandmother, Nancy Hudgins, took great pride in caring for her flowers. Ida’s account comes from a school essay she wrote in 1893, of the garden in the 1870 and 1880s. While some of Nancy’s flower choices were out of fashion for the time, “grandmother did not make her selections to please other people, but these had been the favorite flowers in her youth and she preferred them now.”

Figure 1. Garden sketch of garden of the same era and context as Nancy Hudgins’ garden at Leigh Farm. From “The Garden at Flowery Dale Plantation, Eastern North Carolina, 1835-1878,” by J. B. Flowers, The Magnolia, 1986.

Figure 2. Hyacinth flowers from a book

of plant illustrations

by Robert John Thornton, published in 1807.

Figure 3. These grape hyacinths are growing at Leigh Farm

Park today, along an old fence line. While not true hyacinth, their common name

is hyacinth because they are similar in appearance.

Ida also remembers hyacinths in many colors, and “pulling the long blades…to hear them ‘sing,’” hoping not to be caught. Ida also recalls climbing on the garden’s picket fence to reach the fruit from orchard trees growing around the border. Of course, with all of these childhood antics, the Leigh children were careful not to be “seen by those who would have ‘reported us at headquarters.’” 1

The Garden at West Point on the Eno Meanwhile, the Mangum Garden, in contrast to Nancy’s at the Leigh House, had “a network of narrow paths [that] ran through the confusion of blooms within the picket fence” of the Mangum’s sprawling flower garden. There was also a hammock in the garden, near the home, which is featured in a family portrait Hugh Mangum took around 1895.

Figure 4. The Mangum

Family, c. 1895. In Sallie and Presley Mangum's garden, outside their home at

West Point on the Eno. Photograph by Hugh Mangum.

The garden hosted more than plants though, it was home to a lily pond with gold fish, a rock garden, a sundial, and even a flower shed dedicated to flower care. 2 All of these were typical of gardens in the early 20th century, and were in a constant state of change. One notable contrast was that Leo Mangum recalled mixing several inches of manure from downtown stables with the soil, despite access to popular commercial fertilizer. 3

Figure 5. This

sundial was a gift from Jack Vaughan, to his aunt, Lula Mangum. It was mounted

to a cedar post and stood within the picket fence, where the brick patio is

today. The face of it reads, “My face marks the sunny hours What can you say

for yours.”

Though very different, both gardens were labors of love. They were a place for family to gather, spend time outdoors, and even get a bit of exercise. At Leigh Farm Park, the 150-plus year old scuppernong vine is still producing, the naturalized daffodils bloom year after year, and there is privet everywhere. At West Point, you can find hyacinths, old roses, lilies, daffodils, yucca, and ivies scattered throughout the park. With a keen eye, maybe you’ll spot them when you’re in the park next.

Today, we continue the gardening tradition in the West Point Garden, where we grow and harvest food for members of our community. We partner with Hannah’s Kitchen and Root Causes (Duke Outpatient Food Pantry) during our harvest season, and donate about 300 pounds of produce a year.

_________________________________________________________________________________

1 Kenneth M. McFarland, “The Garden at Leigh Farm,” Bulletin of the Southern Garden History Society VII, no. III (Winter 1991): Appendix 9.

2 “The Mangum’s Garden, as Recalled by Their Descendants: Jack, Polly, Louise, and Vivian Vaughan, Pattie Scarborough and Eddie Rowe” (handwritten document, 1981), West Point Cultural Heritage.

3 Jack Vaughan, “Memories of the Mangum Family Garden,” 1981, West Point Cultural Heritage; and Patricia M. Tice, “Gardens of Change,” in American Home Life, 1880-1930: A Social History of Spaces and Services, ed. Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 190–208.

Comments

Post a Comment